Artificial Reefs of Delaware: What’s Beneath the Surface

This content was provided by Bridget FitzPatrick of Delaware Retiree! Visit their vibrant site at delawareretiree.com for insightful tips and tales perfect for the savvy retiree. Follow on Facebook for compelling articles, local groups, and events. Or subscribe to their newsletter through their website to get savvy content delivered quarterly to your inbox!

Next time you board the Cape May – Lewes Ferry or take a boat tour of the waters surrounding the Delaware Bay and Atlantic Ocean, think about this.

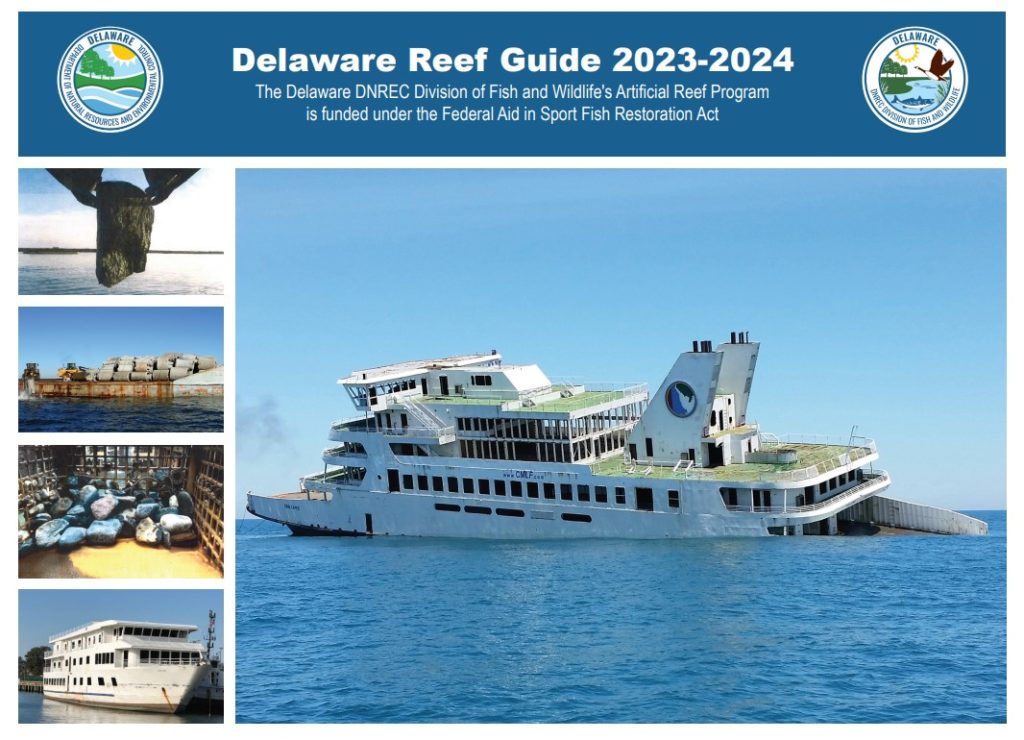

Delaware’s Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) has been focused on what you cannot see from the surface. In 1995, it established an enormous undertaking to enhance the bay and oceanwater environment by building artificial reefs. That work continues today and has had an enormous effect on Delaware’s economy.

Fourteen underwater sites are considered artificial reefs, and the enormity of what’s down there is astounding. Beginning with recycled concrete and concrete products to build up the floor of the bay, DNREC sought to create habitats that encourage marine life.

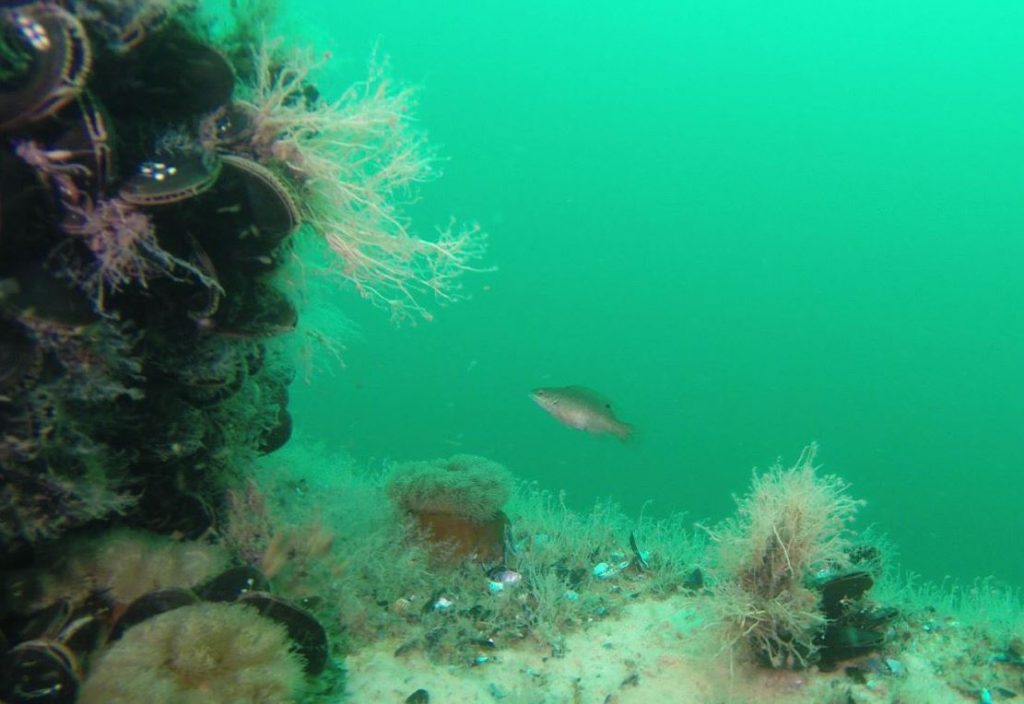

The Mid-Atlantic region generally has a muddy or sandy ocean bottom unlike, for example, the rockier offshore surfaces of New England. By creating artificial reefs that mimic coral reefs or natural rocky coastal barriers, a busier life undersea now takes place with everything from invertebrates such as mussels and oysters to the reef fish that feed on them.

Hence, there’s the economic impact on everything from commercial to recreational fishing to underwater exploration. DNREC estimates a whopping $87 million is added to Delaware’s economy from anglers annually.

The DNREC project began to grow exponentially in the next several years and is ongoing today as they continue to remove bedrock in the navigation channels leading to the Delaware Bay, a process spearheaded by the Army Corps of Engineers.

Here are some interesting facts on what “lurks” in our local waters and has a profoundly positive impact on marine life:

- More than 1,300 51-foot-long retired NYC Metropolitan Transportation Authority subway cars donated to DNREC. One ocean reef is aptly named “The Redbird” due to the iconic shade of red on each subway car.

- 86 decommissioned military vessels, including an ex-destroyer

- A retired Coast Guard Cutter

- The retired Cape May – Lewes ferry, the MV Twin Capes

- Commercial tugboats

- Numerous private and commercial ships ranging from 40 to 653 feet in length

If you are thinking that it sounds like ingredients for a major negative environmental impact, think again. There are very strict environmental standards for cleaning and preparing any sunken vessel.

In addition to the increase in desirable gamefish, many of the reefs have also created a popular destination for SCUBA divers and wreck (or in this case, sunken ship) exploratory sites. There are also standards of vessel stability for obvious safety issues.

Some of the desirable species increases that have occurred include mussels, oysters, tautog, flounder, tuna and striped bass.

All told, there are eight artificial reefs in the Delaware Bay, as far north a Dover, and four more in the Atlantic. The farthest offshore is 55 miles, and the southernmost is off the coast of Fenwick Island. The map and guide available through DNREC shows that the highest concentration of reef sites is generally off the coast of Lewes, where game fishing is quite popular as a result.

More information and maps of the artificial reef sites can be found on DNREC’s website. It is fascinating to learn how even subway cars can be repurposed.